How the World Came to Save Haiti and Left Behind a Disaster (book review)

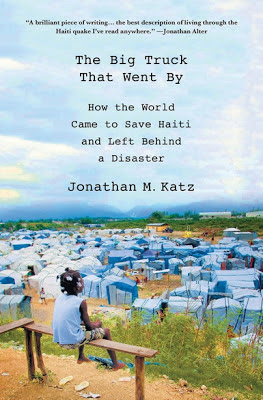

Jonathan Katz’ book The Big Truck That Went By. How The World Came to Save Haiti and Left Behind a Disaster has already received a lot of recognition and positive endorsement and I do agree that his book is an excellent expose of contemporary global humanitarian and development efforts and key systemic flaws.

As a former AP correspondent he lived through the 2010 Haiti earthquake and followed closely the reconstructionefforts machinery that quickly set into motion for one of the world largest aid efforts.

You may have seen the advertising banners on Palgrave’s website (‘Where Did YOUR donation go?’) which I find a bit misleading for the sake of marketing the book to a broader audience.

But this is not the author’s fault, of course, but the story does not really follow ‘your donation’ and it captures the complex nature of post-disaster aid better than simply ‘exposing the failure of foreign aid’ – which the book still manages well.

To give my review a better focus, I will highlight three themes that I found particularly interesting and that made the book an engaging and very worthwhile read beyond the factual content of how post-disaster aid did and did not unfold.

First, and maybe least surprising, Jonathan Katz highlights time and again that aid has always been political and that Haiti in 2010 and beyond is not different. Second, due to his professional lens as journalist he is in an interesting position to engage with the topic of celebrity activists and their involvement in Haiti. And third, as someone who enjoys reflective writing, Jonathan Katz’ style is an excellent example of how journalism and critical writing on the aid industry can be brought together with an involved, reflective approach that does not turn a critical journalist automatically into a ‘frontline hero’.

The political economy of aid pledges and disaster capitalism

Although this may not be breaking news to ‘us’ on the expert side of all things development, it is important to stress that aid is (still) political. So whenever an organization or person claims that they can circumvent the red tape and get straight to ‘those in need’ they are not only not telling the full story, but they also ignore that the structures of ‘those in need’ are also politicised. As Katz illustrates, even a visit to one of the camps can turn into a political exercise when a self-proclaimed camp ‘commander’ wants to talk to the journalist and manages access to the inside of the camp.

We have gotten used to fingerpointing at those at the top when it comes to political manoeuvres, taking advantage or even outright corruption (of which not that much occurred according to Katz), but we often ignore the truth that any social structure comes with power relations and political structures of sorts. Just setting up or engaging with a ‘camp committee’ is no guarantee for fairness – especially in large camps where social structures are often mimicked shortly after an emergency.

But more importantly, Katz provides numerous examples of how ‘pledges of aid’ at a high-level conference do not mean ‘aid for Haiti’ and that ‘aid for Haiti’ does not necessarily mean ‘aid spent directly on the well-being of Haitians’:

And bureaucratic reflexes die hard, very hard. Katz who recently wrote an updated piece on the cholera outbreak together with Tom Murphy features the beginning of this story at the end of his book, as a kind of ‘lowlight’. And sure enough, old bureaucratic reflexes die hard and the UN’s response to the allegations that the outbreak was linked to Nepali peacekeepers was exactly the opposite of transparency or accountability:

At the same time, the book documents well the rise of new aid actors (pun intended...) and celebrities and the chances and limitations their engagement has. In the end, Bill Clinton’s, Sean Penn’s or Wyclef Jean’s engagement is summarized well by Katz’ comment on Sean Penn in the final chapter:

Reflective writing and complexity

Katz deserves praise for his prose which is a good example of how good ‘frontline’ reporting has been changing from a ‘lone wolf’ approach full of Machismo to a more nuanced, at times volatile and vulnerable approach to get a complex story across to the reader. I struggled a bit with the first chapter (with the suitable name ‘The End’), because it is not a linear, organized narrative, but a reflection of the immersion of Katz into the realities of being on the ground when the earthquake struck and the difficult choices many had to make:

Watching the big truck pass by

As a teacher and researcher I thoroughly enjoyed both the style and the substance of the book and I can recommend it highly to any colleague who is looking for a good example for a contemporary discussion on ‘how aid works’ (and often still does not really...).

Jonathan Katz avoids broad and sweeping suggestions in his final reflections, but reminds the reader that investment in functioning local structures are an essential part of ensuring resilience to natural disasters and becoming responsible in case of recovery efforts. He also reminds the (American) consumer once again that the low-wage Haitian garment industry can all too easily be sold as a success story of ‘better than nothing’ when other local initiatives, for example in rural agriculture, are underexplored. As the book comes to an end there is a sad ‘business as usual’ feeling as the ‘big truck’ is passing by and leaving for the next disaster ‘theatre’:

Full disclosure: I asked Jonathan Katz for a review copy which Palgrave Macmillan provided in October 2012.

As a former AP correspondent he lived through the 2010 Haiti earthquake and followed closely the reconstruction

You may have seen the advertising banners on Palgrave’s website (‘Where Did YOUR donation go?’) which I find a bit misleading for the sake of marketing the book to a broader audience.

But this is not the author’s fault, of course, but the story does not really follow ‘your donation’ and it captures the complex nature of post-disaster aid better than simply ‘exposing the failure of foreign aid’ – which the book still manages well.

To give my review a better focus, I will highlight three themes that I found particularly interesting and that made the book an engaging and very worthwhile read beyond the factual content of how post-disaster aid did and did not unfold.

First, and maybe least surprising, Jonathan Katz highlights time and again that aid has always been political and that Haiti in 2010 and beyond is not different. Second, due to his professional lens as journalist he is in an interesting position to engage with the topic of celebrity activists and their involvement in Haiti. And third, as someone who enjoys reflective writing, Jonathan Katz’ style is an excellent example of how journalism and critical writing on the aid industry can be brought together with an involved, reflective approach that does not turn a critical journalist automatically into a ‘frontline hero’.

The political economy of aid pledges and disaster capitalism

Although this may not be breaking news to ‘us’ on the expert side of all things development, it is important to stress that aid is (still) political. So whenever an organization or person claims that they can circumvent the red tape and get straight to ‘those in need’ they are not only not telling the full story, but they also ignore that the structures of ‘those in need’ are also politicised. As Katz illustrates, even a visit to one of the camps can turn into a political exercise when a self-proclaimed camp ‘commander’ wants to talk to the journalist and manages access to the inside of the camp.

We have gotten used to fingerpointing at those at the top when it comes to political manoeuvres, taking advantage or even outright corruption (of which not that much occurred according to Katz), but we often ignore the truth that any social structure comes with power relations and political structures of sorts. Just setting up or engaging with a ‘camp committee’ is no guarantee for fairness – especially in large camps where social structures are often mimicked shortly after an emergency.

But more importantly, Katz provides numerous examples of how ‘pledges of aid’ at a high-level conference do not mean ‘aid for Haiti’ and that ‘aid for Haiti’ does not necessarily mean ‘aid spent directly on the well-being of Haitians’:

Yet most of the money pledged by foreign governments had never been meant for Haitian consumption. [...] in the end at least 93% [of $2.43 billion] would go right back to the UN or NGOs to pay for supplies and personnel. [...] Just one percent – slightly over $24 million – went to the Haitian government. [...] Haiti’s private sector fared even worse. Of the nearly $1 billion in U.S. government contracts for postquake Haiti, just twenty-two, worth less than $4.8 million, went to Haitian firms. [...] Unusually for a disaster, a major chunk of U.S. government spending went through the Defense Department: $465 million through August 2010, mostly to the usual contractors or for standard deployment expenses. [...] But it’s misleading to call such spending “money for Haiti” especially when it gives the impression that any Haitian could have misappropriated or even profited from it (204-205).Throughout his book Katz illustrates the power of ‘old aid’ well: When aid pledges are made, foreign investors are approached and politics are discussed the big players come together – not venture capitalists, do-it-yourself aid workers or (mis)guided do gooders. As I have highlighted elsewhere, old aid organizations and structures still deserve our critical attention even if new, ‘sexier’ initiatives capture our imagination of a new aid world.

And bureaucratic reflexes die hard, very hard. Katz who recently wrote an updated piece on the cholera outbreak together with Tom Murphy features the beginning of this story at the end of his book, as a kind of ‘lowlight’. And sure enough, old bureaucratic reflexes die hard and the UN’s response to the allegations that the outbreak was linked to Nepali peacekeepers was exactly the opposite of transparency or accountability:

The [independent] panel [that looked into the outbreak] was missing the smoking gun, and in this sense, the cover-up [of the UN] had worked. The initial refusal to investigate and the attempts to stifle inquiry had left researchers with no evidence of Vibrio cholerae at the base itself (243).The spectacular rise of celebrity aid efforts

At the same time, the book documents well the rise of new aid actors (pun intended...) and celebrities and the chances and limitations their engagement has. In the end, Bill Clinton’s, Sean Penn’s or Wyclef Jean’s engagement is summarized well by Katz’ comment on Sean Penn in the final chapter:

His powers as a foreigner, greatly bolstered by his international celebrity, have allowed the actor to gain a level of influence far beyond his qualifications or expertise (281).The aid industry needs to be prepared for more celebrity involvement and maybe celebrities will start to realize that they need to liaise with topical experts and non-celebrity researchers and aid workers to ensure a sustainable impact.

Reflective writing and complexity

Katz deserves praise for his prose which is a good example of how good ‘frontline’ reporting has been changing from a ‘lone wolf’ approach full of Machismo to a more nuanced, at times volatile and vulnerable approach to get a complex story across to the reader. I struggled a bit with the first chapter (with the suitable name ‘The End’), because it is not a linear, organized narrative, but a reflection of the immersion of Katz into the realities of being on the ground when the earthquake struck and the difficult choices many had to make:

I knew people who made different choices: A freelance photographer has left his camera for a pickax. That night I believed that my greatest responsibility was to report the news, so the outside world might comprehend the scale and urgency of the crisis and send help. It was a duty I thought important, maybe noble, even if fulfilling it meant my career would profit. I thought I would be of more use that way to the desperate people around me. In hindsight, I’m not sure. And that’s the one great truth revealed in moments like that one: You always have to choose, and you will never know (27).In the end, Katz does not know all the answers and he certainly is no ‘hero’ who claims to give someone ‘a voice’. Critical writing on development issues certainly can do with more of this philosophy.

Watching the big truck pass by

As a teacher and researcher I thoroughly enjoyed both the style and the substance of the book and I can recommend it highly to any colleague who is looking for a good example for a contemporary discussion on ‘how aid works’ (and often still does not really...).

Jonathan Katz avoids broad and sweeping suggestions in his final reflections, but reminds the reader that investment in functioning local structures are an essential part of ensuring resilience to natural disasters and becoming responsible in case of recovery efforts. He also reminds the (American) consumer once again that the low-wage Haitian garment industry can all too easily be sold as a success story of ‘better than nothing’ when other local initiatives, for example in rural agriculture, are underexplored. As the book comes to an end there is a sad ‘business as usual’ feeling as the ‘big truck’ is passing by and leaving for the next disaster ‘theatre’:

The Interim Haiti Recovery Commission’s mandate ended, having approved $3.2 billion worth of projects – a third of which were left unfunded. Neither a Haitian-led commission, nor anything else, replaced it’ (280).All in all, Jonathan Katz wraps up with a thoughtful analysis that the ‘big truck that went by’ was not just aid business as usual, but will probably slightly worse in the longer term:

The enormous talent, money, and goodwill of the post-quake response left an ironic legacy in Haiti. Having sought above all to prevent riots, ensure stability, and prevent disease, the responders helped spark the first, undermine the second, and by all evidence caused the third (278-279).Katz, Jonathan M.: The Big Truck That Went By: How the World Came to Save Haiti and Left Behind a Disaster, ISBN: 978-0-230-34187-6, 320 pages, $26.00, Palgrave Macmillan.

Full disclosure: I asked Jonathan Katz for a review copy which Palgrave Macmillan provided in October 2012.

Comments

Post a Comment