Representation of aid in/and pop culture: Reading Living Level-3

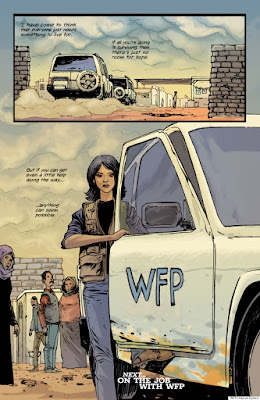

Similar to J. who already posted some reflections on the WFP-sponsored graphic novel Living Level-3: Iraq my first impressions of the novel (or the first four parts that have been published on the Huffington Post so far) are relatively positive-with a few caveats, of course.

Aid work as outdoor life

When WFP expat aid worker Leila, an American citizen, declares

The power of stories, ICT-and guns

But the four chapters also manage to balance the Lara Croft-style outdoor vehicle action with calmer and intensive moments: Leila sitting in the background during a meeting with a Kurdish politician or comforting a woman whose daughter have been kidnapped (‘I have nothing to live for’-again, the writing could have been stronger…).

And when Khaled and Hakima receive a call from their son Nasser (‘When I hear my son’s voice it feels like dawn warmth after a long night’-finally the writing is matches the emotions!) the stupid ‘refugees have mobile phones and are well off’ debate should finally be put to rest.

Even though the work is surprisingly un-digital, the power of ICT is present in a couple of scenes.

A theme that also emerges more clearly in the fourth part is that the traditional dichotomy ‘bad guys have guns-good people use non-violent means’ is challenged when the Peshmergas break the siege at Sinjar. These nuances and hints at the complexities of humanitarian crises are quite important to highlight.

Aid in the 21st century-how much ‘listening’ can we be doing & how do we avoid creating new stereotypes around aid work?

As J. rightly pointed out all the imperfections aside, this is a graphic aid novel for our times.

Popular representations of any profession almost always fail to capture the less glamorous and more dull moments of a job-hospital shows take place in the operating theater, high school teaching consists of classroom teaching and college professors are rarely seen grading a big pile of OK-ish essays. Professional humanitarian and aid work needs to be judged against general pop-cultural archetypes and sometimes stereotypes, rather than claiming an extra important space for it.

WFP and its work is and works among ourselves and Leila is doing a pretty good job most of the time-even though it is heavy on the one-woman-show element and teamwork with (local) colleagues would have been added a nice touch as would have a note on self-care and mental/physical well-being.

There is an inherent risk of creating new stereotypes of what aid work and aid workers look like through graphic novel ‘heroines’. Leila seems to be working more than one job as well as on different career- and pay-levels at the same time at the beginning of her assignment.

The concept of ‘listening’ is featured quite heavily throughout the novel-maybe as a representation of how today’s aid work works. Leila’s story between ‘finding herself’ as an Egyptian-American expat aid worker, the real humanitarian demands in Iraq and a world where ‘our aid’ will not necessarily solve ‘their’ and our problems is a story fit for 2016 discussions on these topics and I look forward to discussing them with students and colleagues in more detail!

Aid work as outdoor life

When WFP expat aid worker Leila, an American citizen, declares

Back home I had everything I could want but still felt lost somehow like I needed purposeI already had an eye-rolling moment right at the beginning. Maybe I have to blame the genre ‘graphic novel’ for this, but I found the writing generally much weaker than the visualizations and the overarching elements of the story. But as one commentator summarized on facebook (admittedly in a more sarcastic way (see her comment below):

I'd be happy to hire this aid worker. She's kick ass, cool, smart, sensitive and a real do-gooder.Her job as a junior VAM (Vulnerability Analysis and Mapping) officer takes Leila straight to humanitarian frontlines in Northern Iraq. I mean ‘straight’in the literal sense: With the exception of a very brief stop-over at the UN compound in Erbil, her journey takes her from Istanbul airport to the frontlines-and every aspect of her work takes place outside, notebook and radio as the only tools to perform her job. This theme continues as WFP’s work is generally depicted as a purely outdoor activity-from airdrops, to helicopter lifts to tanker trucks with fresh water WFP is always in motion.

The power of stories, ICT-and guns

But the four chapters also manage to balance the Lara Croft-style outdoor vehicle action with calmer and intensive moments: Leila sitting in the background during a meeting with a Kurdish politician or comforting a woman whose daughter have been kidnapped (‘I have nothing to live for’-again, the writing could have been stronger…).

And when Khaled and Hakima receive a call from their son Nasser (‘When I hear my son’s voice it feels like dawn warmth after a long night’-finally the writing is matches the emotions!) the stupid ‘refugees have mobile phones and are well off’ debate should finally be put to rest.

Even though the work is surprisingly un-digital, the power of ICT is present in a couple of scenes.

A theme that also emerges more clearly in the fourth part is that the traditional dichotomy ‘bad guys have guns-good people use non-violent means’ is challenged when the Peshmergas break the siege at Sinjar. These nuances and hints at the complexities of humanitarian crises are quite important to highlight.

Aid in the 21st century-how much ‘listening’ can we be doing & how do we avoid creating new stereotypes around aid work?

As J. rightly pointed out all the imperfections aside, this is a graphic aid novel for our times.

Popular representations of any profession almost always fail to capture the less glamorous and more dull moments of a job-hospital shows take place in the operating theater, high school teaching consists of classroom teaching and college professors are rarely seen grading a big pile of OK-ish essays. Professional humanitarian and aid work needs to be judged against general pop-cultural archetypes and sometimes stereotypes, rather than claiming an extra important space for it.

WFP and its work is and works among ourselves and Leila is doing a pretty good job most of the time-even though it is heavy on the one-woman-show element and teamwork with (local) colleagues would have been added a nice touch as would have a note on self-care and mental/physical well-being.

There is an inherent risk of creating new stereotypes of what aid work and aid workers look like through graphic novel ‘heroines’. Leila seems to be working more than one job as well as on different career- and pay-levels at the same time at the beginning of her assignment.

The concept of ‘listening’ is featured quite heavily throughout the novel-maybe as a representation of how today’s aid work works. Leila’s story between ‘finding herself’ as an Egyptian-American expat aid worker, the real humanitarian demands in Iraq and a world where ‘our aid’ will not necessarily solve ‘their’ and our problems is a story fit for 2016 discussions on these topics and I look forward to discussing them with students and colleagues in more detail!

Oh...my bad. This commentator meant to be sarcastic in hiring Leila. I was eye rolling. Leila doesn't exist....I like how they've written a junior VAM officer this way. Leila really does not exist....if she did, I would hire her. I think I'm pretty good and I'd hire me but even I'm not Leila. Good commentary above. Enjoyed reading it.

ReplyDeleteThanks...luckily it's a blog post so I added a note on sarcasm and pointed at your comment!

Delete