Shame (book review & discussion with author Jillian Reilly)

One of my personal highlights of our recent trip to South Africa was the discussion I had with (former) aid worker and author Jillian Reilly.

We took her biography as the starting to discuss aid work as a career, entering the industry before it really was one, becoming a reflective practitioner, leaving the industry and writing a very interesting book about it all. I will start with my review before introducing our discussion.

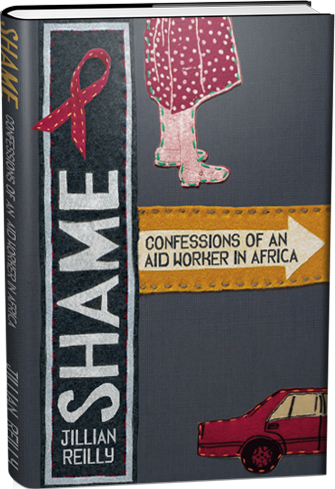

Shame – Confessions of an aid worker in Africa

Books on aid work and aid workers are an important genre for my book reviews. What intrigued me with Jillian Reilly’s book right from the start was that it avoids the crisis-hopping Bosnia-to-Rwanda-to-Afghanistan-to-Haiti routine that often goes hand in hand with the humanitarian theatre of parties, adrenaline, coordination meetings and some sort of unkempt romantic entanglement.

Jillian focuses on more mundane development work and her personal journey from an eager volunteer in the first South African election after the end of Apartheid to being (or maybe more precisely: being identified) as an ‘HIV/AIDS expert’ in Zimbabwe. In some ways it is a typical aid worker biography, but that does not make it any less readable in the context of reflecting on aid worker, their expertise and the growth of the industry in the last 20 or so years.

Jillian enters international travel and development through the thriving ‘democracy industry’ of the post-Cold War 1990s. As a recent graduate from an American university she sets out to ‘do good’ in Africa and an internship (yes, those already existed 20 years ago…) with a South African legal aid NGO that educates prison inmates about their new democratic rights. Amid rapid social change and racist white neighbors Jillian quickly encounters some of those dilemmas, complexities and unresolvable situations that aid work always has to offer underneath a seemingly clear moral compass of ‘doing good’.

But only after her move to Johannesburg does she become a part of the rapidly growing development industry. She is primarily hired for grant and report writing and her first boss is fully aware of the situation:

Jillian’s encounters of becoming an ‘AIDS expert’ without much of a technical, medical or programming background really captured my attention and I was wondering whether she was part of a last generation of aid workers who could enter and maintain work in the industry with good intentions and self-learning skills, but without a ‘background’ of development. As much as professionalization is an important issue the question remains whether aid work has really become ‘better’ or more impactful.

Her relationship with a ANC activist is the entry point for reflections that combine her individual journey with key emerging discourses around aid work and aid workers: Her North American quest for a ‘vision’ and a personal and professional ‘plan’ (p.157) in a difficult cultural and political context (‘We’re not like you Americans who believe you have complete control over your lives’ as a workshop participant remarks (p.195); the challenge that HIV/AIDS prevention and education is not just an abstract ‘deliverable’, but ultimately deals with deep-rooted gender-, economic- and cultural biases in a context where ‘nobody talks about their real (sex) life in the workshops’ (p.175)-no matter how fun, ‘empowering’ or even entertaining they are.

In the end, Jillian Reilly is concerned about her well-being, close to a burn-out and tired of white lies to perform her expertise and leaves the aid industry. There is no grand finale, but a self-described end of a ‘coming-of-age’ story that is probably quite typical for the ‘unknown aid workers’ who have silently left the industry over the years.

All in all, I can highly recommend Jillian’s book-it is a well-written, entertaining aid worker memoir that takes place at a unique historical juncture for South and Southern Africa and unfolds a nuanced, grounded reflection about the industry that aims at a bigger picture rather than exciting war-zone vignettes or refugee camp anecdotes.

In late March 2014 Jillian and I met for the first time in a small café on one of the picturesque main streets in Stellenbosch, South Africa. When she picks me up in her Landrover Discovery from Stellenbosch University’s modern conference facility there is an odd moment of cosmopolitan awareness of opportunity and potential privilege that both of us have enjoyed and that the global aid and education industries have facilitated in strange ways.

Are we making ‘a difference’ here or wherever we travel, work, teach and talk?

Reilly, Jillian (2012): Shame. Confessions Of An Aid Worker in Africa. ISBN 978-1-4717-6656-5, 233 pages, USD 11.95 (Kindle Edition), Moonshine Media, South Africa.

Aid worker memoirs as emerging genre and the challenges of reflexive writing

Jillian and I talked for about 45 minutes during our Comdev seminar at RLabs in Bridgetown.

I am not attempting to summarize the talk, but at least I can provide you with an idea about some of the topics we discussed and where to find them in the video:

TD: Introduction & general remarks on aid worker literature as an emerging genre (00:00–11:00)

JR: Introduces her book: Questions about motivation, representation/representativeness, relationships and human connections (11:00–33:00)

TD/JR discussion: Professionalization and technocratisation of aid work; sex/pleasure/reproductive health; aid worker power dynamics (34:00–43:00)

Discussion with audience: What about books written by aid recipients rather than donors?; how paternalistic is aid (still?) (43:00-55:00) & more (55:00-1:13:00).

We took her biography as the starting to discuss aid work as a career, entering the industry before it really was one, becoming a reflective practitioner, leaving the industry and writing a very interesting book about it all. I will start with my review before introducing our discussion.

Shame – Confessions of an aid worker in Africa

Books on aid work and aid workers are an important genre for my book reviews. What intrigued me with Jillian Reilly’s book right from the start was that it avoids the crisis-hopping Bosnia-to-Rwanda-to-Afghanistan-to-Haiti routine that often goes hand in hand with the humanitarian theatre of parties, adrenaline, coordination meetings and some sort of unkempt romantic entanglement.

Jillian focuses on more mundane development work and her personal journey from an eager volunteer in the first South African election after the end of Apartheid to being (or maybe more precisely: being identified) as an ‘HIV/AIDS expert’ in Zimbabwe. In some ways it is a typical aid worker biography, but that does not make it any less readable in the context of reflecting on aid worker, their expertise and the growth of the industry in the last 20 or so years.

Jillian enters international travel and development through the thriving ‘democracy industry’ of the post-Cold War 1990s. As a recent graduate from an American university she sets out to ‘do good’ in Africa and an internship (yes, those already existed 20 years ago…) with a South African legal aid NGO that educates prison inmates about their new democratic rights. Amid rapid social change and racist white neighbors Jillian quickly encounters some of those dilemmas, complexities and unresolvable situations that aid work always has to offer underneath a seemingly clear moral compass of ‘doing good’.

But only after her move to Johannesburg does she become a part of the rapidly growing development industry. She is primarily hired for grant and report writing and her first boss is fully aware of the situation:

‘Every INGO in Jo’burg is filled with smart, skill-less people like you’ (p.73).Her promotion to manage the organization’s program in Zimbabwe happens at a time that to me seemed almost nostalgically distant: A pre-9/11 world in which the U.S. and American aid are still praised for their efforts to promote democracy and build capacity in Africa-an interesting reminder of how deep-rooted the damage is that the ‘war on terror’ has caused.

Jillian’s encounters of becoming an ‘AIDS expert’ without much of a technical, medical or programming background really captured my attention and I was wondering whether she was part of a last generation of aid workers who could enter and maintain work in the industry with good intentions and self-learning skills, but without a ‘background’ of development. As much as professionalization is an important issue the question remains whether aid work has really become ‘better’ or more impactful.

Her relationship with a ANC activist is the entry point for reflections that combine her individual journey with key emerging discourses around aid work and aid workers: Her North American quest for a ‘vision’ and a personal and professional ‘plan’ (p.157) in a difficult cultural and political context (‘We’re not like you Americans who believe you have complete control over your lives’ as a workshop participant remarks (p.195); the challenge that HIV/AIDS prevention and education is not just an abstract ‘deliverable’, but ultimately deals with deep-rooted gender-, economic- and cultural biases in a context where ‘nobody talks about their real (sex) life in the workshops’ (p.175)-no matter how fun, ‘empowering’ or even entertaining they are.

In the end, Jillian Reilly is concerned about her well-being, close to a burn-out and tired of white lies to perform her expertise and leaves the aid industry. There is no grand finale, but a self-described end of a ‘coming-of-age’ story that is probably quite typical for the ‘unknown aid workers’ who have silently left the industry over the years.

All in all, I can highly recommend Jillian’s book-it is a well-written, entertaining aid worker memoir that takes place at a unique historical juncture for South and Southern Africa and unfolds a nuanced, grounded reflection about the industry that aims at a bigger picture rather than exciting war-zone vignettes or refugee camp anecdotes.

In late March 2014 Jillian and I met for the first time in a small café on one of the picturesque main streets in Stellenbosch, South Africa. When she picks me up in her Landrover Discovery from Stellenbosch University’s modern conference facility there is an odd moment of cosmopolitan awareness of opportunity and potential privilege that both of us have enjoyed and that the global aid and education industries have facilitated in strange ways.

Are we making ‘a difference’ here or wherever we travel, work, teach and talk?

Reilly, Jillian (2012): Shame. Confessions Of An Aid Worker in Africa. ISBN 978-1-4717-6656-5, 233 pages, USD 11.95 (Kindle Edition), Moonshine Media, South Africa.

Aid worker memoirs as emerging genre and the challenges of reflexive writing

Jillian and I talked for about 45 minutes during our Comdev seminar at RLabs in Bridgetown.

I am not attempting to summarize the talk, but at least I can provide you with an idea about some of the topics we discussed and where to find them in the video:

TD: Introduction & general remarks on aid worker literature as an emerging genre (00:00–11:00)

JR: Introduces her book: Questions about motivation, representation/representativeness, relationships and human connections (11:00–33:00)

TD/JR discussion: Professionalization and technocratisation of aid work; sex/pleasure/reproductive health; aid worker power dynamics (34:00–43:00)

Discussion with audience: What about books written by aid recipients rather than donors?; how paternalistic is aid (still?) (43:00-55:00) & more (55:00-1:13:00).

Comments

Post a Comment