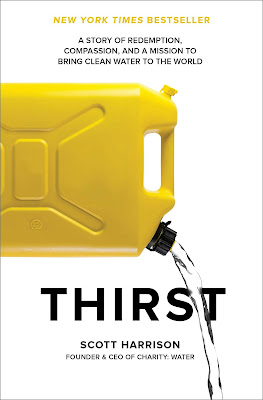

Thirst (book review)

After I watched a quite terrible

promotional video from charity: water and ended up buying its founder

and CEO’s biography Thirst. A Story of Redemption, Compassion, and a Mission toBring Clean Water to the World I was prepared for the worst.

But despite my extensive readings of aid worker biographies and a fairly critical approach towards ‘disruptive’ charitable ideas in development Thirst surprised me in some ways.

It is one of the most, for lack of a better word, schizophrenic development tales I have read in a long time, the tale of a 21st century charity that fundraises millions and positively impacts the lives of millions-and a tale about a lot of things that are going wrong in contemporary development whenever a white American man is looking for ‘redemption’ and needs to find it in a village in Africa.

Thirst is definitely a book you should read, but with a different educational trajectory in mind perhaps than the author intended; rather than seeing Harrison’s journey purely as a tale of ‘inspiration’ and background for donations to his charity, this is maybe a tale to raise questions about how we want global development relationships to look like and what running a charity means in the 21st century.

But despite my extensive readings of aid worker biographies and a fairly critical approach towards ‘disruptive’ charitable ideas in development Thirst surprised me in some ways.

It is one of the most, for lack of a better word, schizophrenic development tales I have read in a long time, the tale of a 21st century charity that fundraises millions and positively impacts the lives of millions-and a tale about a lot of things that are going wrong in contemporary development whenever a white American man is looking for ‘redemption’ and needs to find it in a village in Africa.

Thirst is definitely a book you should read, but with a different educational trajectory in mind perhaps than the author intended; rather than seeing Harrison’s journey purely as a tale of ‘inspiration’ and background for donations to his charity, this is maybe a tale to raise questions about how we want global development relationships to look like and what running a charity means in the 21st century.

The New York nightclub promoter who discovers a spiritual void in his life

There is no easy way to say this, but after

struggling through the first part of the book (the first 75 pages) I was close

to giving up. The story of a New York City night club promoter wanting more

from his American life and discovering the ‘charity’ sector raised my blood

pressure and fear of how terrible his journey may end.

Another rejection! My third this week. Ever since coming home, I’d learned that volunteering wasn’t as easy as it sounded.“No charity wants me,” I told my dad. “I guess promoting nightclubs isn’t high on the list of skills they’re looking for.” (p.68)

In the end, Harrison is becoming a volunteer

photographer and communication person for Mercy Ships, a hospital ship-focused

charity that sails the seas of Africa to provide free surgeries, specializing

on tumors and other facial ailments that often ostracize people and severely

impede their health and well-being.

Harrison matures in his role, setting up

fundraisers through his New York networks built during his nightclub promoting

days.

There are a lot of people who like a good story of personal transformation and helping kids in Africa and are happy to open their wallets for a good cause. That model of raising money in the global North and passing it on to projects in Africa remains the backbone of Harrison’s work.

Such a model can achieve some great things, but its limitations, especially regarding the broader framework outside a successful project, are never addressed.

There are a lot of people who like a good story of personal transformation and helping kids in Africa and are happy to open their wallets for a good cause. That model of raising money in the global North and passing it on to projects in Africa remains the backbone of Harrison’s work.

Such a model can achieve some great things, but its limitations, especially regarding the broader framework outside a successful project, are never addressed.

And then he strikes, well, water…

We had no cash, but plenty of energy and way too much confidence…It felt like building a start-up…I was on a mission, with no bureaucracy or approval process to slow me down…My story read like a satire from The Onion…

The signs and handouts promised that 100 percent of every purchase would go toward building wells with our NGO partners in Uganda, Ethiopia, Malawi, and Central African Republic. (pp.144-152)

Setting up charity: water certainly

comprises some recognizable start-up elements, how it grows out of someone’s

New York loft to a global operation, how personal, professional and organizational

identities are always fluid, how surprisingly little input there is from

experts who know the subject and how even in this day and age traditional

relationships with ‘beneficiaries’ are maintained through sending money from New York to the ‘field’ with little overhead.

But this is also the part that explains how

charity: water did not turn into another Kony2012 or Hollywood celebrity vanity

project; this part is not about orphanages, celebrity ambassadors and someone’s

slightly imperial dream of running a charity from their big house in Cape Town

or Nairobi because they ‘fell in love with Africa’.

The rise of charity: water goes hand in hand with the ‘disruption’ of the charitable sector.

Harrison’s product of clean water is probably what children were to UNICEF in the 1980s-it is an ingenious marketing tool that hits the nerve of the time.

From selling water bottles to establishing a platform for individual fundraising campaigns to tapping into wealthy donors and re-telling the story of wells and clean water in a modern way is a source that keeps on giving. Just like AirB’n’B ‘disrupted’ couch surfing and Uber revolutionized ‘taking a taxi’, charity: water is re-inventing the development trope of ‘building a well in an African village’.

The rise of charity: water goes hand in hand with the ‘disruption’ of the charitable sector.

Harrison’s product of clean water is probably what children were to UNICEF in the 1980s-it is an ingenious marketing tool that hits the nerve of the time.

From selling water bottles to establishing a platform for individual fundraising campaigns to tapping into wealthy donors and re-telling the story of wells and clean water in a modern way is a source that keeps on giving. Just like AirB’n’B ‘disrupted’ couch surfing and Uber revolutionized ‘taking a taxi’, charity: water is re-inventing the development trope of ‘building a well in an African village’.

I wanted to build an optimistic, imaginative, hopeful organization that people would donate to because they felt empowered and inspired-not because we’d guilted them into it. (p.161)

Like the pinkification of breast cancer

awareness, the commodification of mindfulness or the depoliticization of

Oprah’s book club, this mix of American ‘can-do-ism’, a good dose of ignoring

learnings from the past and a firm neoliberal outlook that avoids any tough

political questions (I don’t think ‘climate change’ or any other cause for dry

wells is mentioned in the book) are bound to write a charitable success story!

Water is always a source of life-never one

of conflict or power. Wells are not part of broader civilian infrastructure,

but holes in the ground that at worst pose technical challenges.

And similar to Silicon Valley-invented platforms all of this can be managed by a group of spiritual, dedicated Americans from an old printing warehouse in New York City.

And similar to Silicon Valley-invented platforms all of this can be managed by a group of spiritual, dedicated Americans from an old printing warehouse in New York City.

A charity for the age of platform- & philanthro-capitalism

Harrison admits that he ‘was terrible at

managing people’ (p.166). His future wife Vik ‘outworked all of us’ (p.184)

when she starts as a volunteer and the team ‘were hardworking novices who

figured it out as we went along’ (p.210). As the organization grows and brings

in double-digit million dollars of annual donations charity: water is

professionalizing:

We needed someone with years of international NGO expertise-in other words, a bureaucrat, but without all the baggage.

But not those people who

Having worked for top global NGOs, but then they’d expect to clock out at 5 p.m. (p.260).

Charity: water does not cooperate with

other NGOs or builds capacity in the countries they work in; they also do not

seem to attend development conferences or talk with academic water experts. I

am not saying they must, but it is this schizophrenic nature of the

organization raising 43 million dollars in 2014 (‘a couple of Twitter’s

employees and investors had donated generously’ after the IPO (p.279), building

lots of wells, significantly increasing sustainability of these wells and still

being a traditional outfit that sends money to Africa.

At the end of the book there is no easy

resolution.

Thirst is food for thought, excellent to discuss with students or non-development experts to have a debate about ‘charity’, about lessons learned from past decades of development and why charity: water is such a successful story-yet fails to really reinvent development, solidarity and giving in the 21st century.

Thirst is food for thought, excellent to discuss with students or non-development experts to have a debate about ‘charity’, about lessons learned from past decades of development and why charity: water is such a successful story-yet fails to really reinvent development, solidarity and giving in the 21st century.

I should probably give credit to co-writer

Lisa Sweetingham and everybody from the editorial team who turned Thirst into

such a good, quick read that leaves me with inspiring stories of the power of

clean water and the frustrations about the ways development, disrupted or not,

should be more political, transformative and inclusive perhaps at the expense

of slower growth and more reflection.

Harrison, Scott: Thirst: A Story of Redemption, Compassion, and a Mission to Bring Clean Water to the World. ISBN 978-1-5247-6284-1, 322pp, 22.95 USD, New York, NY: Currency, 2018.

Harrison, Scott: Thirst: A Story of Redemption, Compassion, and a Mission to Bring Clean Water to the World. ISBN 978-1-5247-6284-1, 322pp, 22.95 USD, New York, NY: Currency, 2018.

Comments

Post a Comment