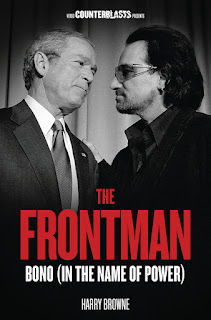

The Frontman-Bono (in the name of power) (book review)

It is fair to say that Bono is one of the leading global celebrities involved in the aid industry and probably one of the founding fathers of modern, celebrity/musician engagement in international humanitarian and development issues.

Harry Browne dedicates a detailed and critical analysis of Bono as part of Verso Books’ ‘Counterblasts’ series.

Since I already reviewed a critical treatment of Jeff Sachs in that series, The Frontman-Bono (In the Name of Power) provides a good opportunity to reflect on celebrity engagement beyond the Irish pop cultural icon and front man of the band U2.

For readers of this blog and those who generally keep a critical eye on popular and public (re)presentations of development, Browne’s rationale behind his critical expose reads hardly surprising:

Since I am not a music buff and really do not have any emotional connection to U2 I find the first part about the emergence of U2 in Ireland just a necessary introduction to the subject. It is noteworthy, however, that U2 emerged in the realm of Irish middle class rather than as a rags to riches story of real social struggle. Basically,

Africa

But then again it is also very possible that things unfolded much less strategic. At the beginning of the second part Browne shares some interesting observations:

All in all, the second part is a really good case study exemplifying the ‘model for conjoining commercial consumption with pseudo-activism’ (p.87)-Bono the philanthrocapitalist between a trip to Africa with World Vision, endorsing RED products, appearing in TED talks and suggesting some kind of Oscar for Kony2012’s Jason Russell. In a similar way as Jeffrey Sachs becomes an embodiment of our aspirations and intellectual efforts to ‘eradicate poverty’, Bono emerges as a pop-cultural personification of the small good deeds ‘everybody’ can do to make ‘development’ happen. The new prophets of capital, which I reviewed recently, is a good introduction to the topic of philanthrocapitalism.

The world

Once names like Rupert Murdoch, Bill Clinton and Apple enter the stage in the third part we can follow the globalization of Bono’s efforts from the mid-2000s onward. From Tony Blair to George Bush and Bill Clinton, Bono’s ‘career’, the

Are Bono & Co worth the critical intellectual effort?

As much as I enjoyed reading Browne’s expose, the book sometimes strays away from ‘The Frontman’ and rather uses his persona as an entry point for a broader critique of development efforts, campaigning and celebrity engagement that go far beyond the power of an individual or any strategic intentions he may have. That’s perfectly fine, although as I mentioned at the beginning, for those with some interest in the topic it may become a bit redundant.

In the end, this is another great contribution to a series that manages to find the right balance of sometimes polemically engaging with ‘front men’ of development and at the same time holding a mirror in front of us to critically check our own standpoints and comfort zones of how much ‘social change’ we really want and how our discourses have become celebritized, mediatized and professionalized without challenging the foundations of inequality and ‘underdevelopment’.

Harry Browne dedicates a detailed and critical analysis of Bono as part of Verso Books’ ‘Counterblasts’ series.

Since I already reviewed a critical treatment of Jeff Sachs in that series, The Frontman-Bono (In the Name of Power) provides a good opportunity to reflect on celebrity engagement beyond the Irish pop cultural icon and front man of the band U2.

For readers of this blog and those who generally keep a critical eye on popular and public (re)presentations of development, Browne’s rationale behind his critical expose reads hardly surprising:

For nearly three decades as a public figure (…) Bono has been (…) amplifying elite discourses, advocating ineffective solutions, patronizing the poor and kissing the arses of the rich and powerful. He has been generating and reproducing ways of seeing the developing world, especially Africa (p.4)Ireland

(…)

the point of this book is to place him and, by extension, celebrity humanitarianism firmly in the realm of politics, and therefore of political difference (p.5).

Since I am not a music buff and really do not have any emotional connection to U2 I find the first part about the emergence of U2 in Ireland just a necessary introduction to the subject. It is noteworthy, however, that U2 emerged in the realm of Irish middle class rather than as a rags to riches story of real social struggle. Basically,

The four boys in U2 (…) were not very different from most people who would become their fans across Europe and North America: comfortably off, liberally raised, and drawn inexorably to the international language of rock ‘n’ roll (p.13).When the first critical treatments in the Irish press emerged around the band’s tax avoidance and real estate dealings, it is possible to think that Bono’s initial engagement with/for Africa started as a form of ‘corporate social responsibility’ even before the term was invented…

Africa

But then again it is also very possible that things unfolded much less strategic. At the beginning of the second part Browne shares some interesting observations:

What’s striking in retrospect is that, in those eighteen minutes (on the Live Aid stage), the man who later attached Africa so definitely to his image makes no effort to connect with the African mission of Live Aid (…). If it were not for the familiar dark silhouette of Africa on the stage backdrop, you could not differentiate this from any other performance (p.60).Bono and celebrity humanitarianism are always a reflection of what we want such performances to be; they are a mirror for our hopes and wishes in the liminal space between entertainment, the resolution of a problem within the attention span of a music video or pop-cultural performance and serious, deep-rooted political engagement. It is our desire to look for a ‘bigger picture’, a moment, sound bite or person that is bigger than us or any global problem which enables celebrity engagement with ‘development’. And it needs experienced performers to find that delicate balance of elevating a crowd without alienating them, of challenging their view just a little bit without condescendingly dismissing their lifestyles and expectations that makes Bono’s engagement appealing, credible-but ultimately nothing more than re-arranging a few consumerist deck chairs on underdevelopment’s Titanic.

(…)

It tells us all too much about delusions fostered by Live Aid that an embrace between a rich rock star and a London fan could be constructed as somehow symbolizing the unity of the world in this moment, a unity somehow connected to providing relief to the absent, hungry ‘they’ living in the dark continent outlined behind the stage. The idea that the girl in the crowd has been singled out for ‘rescue’ by him from an allegedly dangerous crush grew over the years, and added further messianic significance to the moment; in fact he had often pulled women fro audiences to dance with them (p.61).

All in all, the second part is a really good case study exemplifying the ‘model for conjoining commercial consumption with pseudo-activism’ (p.87)-Bono the philanthrocapitalist between a trip to Africa with World Vision, endorsing RED products, appearing in TED talks and suggesting some kind of Oscar for Kony2012’s Jason Russell. In a similar way as Jeffrey Sachs becomes an embodiment of our aspirations and intellectual efforts to ‘eradicate poverty’, Bono emerges as a pop-cultural personification of the small good deeds ‘everybody’ can do to make ‘development’ happen. The new prophets of capital, which I reviewed recently, is a good introduction to the topic of philanthrocapitalism.

The world

Once names like Rupert Murdoch, Bill Clinton and Apple enter the stage in the third part we can follow the globalization of Bono’s efforts from the mid-2000s onward. From Tony Blair to George Bush and Bill Clinton, Bono’s ‘career’, the

phenomenon of Bono is profoundly linked to efforts over recent decades by Western leaders, both in and out of political office, to project themselves as humanitarian visionaries (p.156).From RED to the ONE campaign, Bono’s efforts continue, but in an increasingly crowded market place for development humanitarianism only time will tell how strong his brand is and how he will reinvent himself to continue as an icon for feel-good consumerism and short-term capitalistic ‘solutions’ to ‘end poverty’.

Are Bono & Co worth the critical intellectual effort?

As much as I enjoyed reading Browne’s expose, the book sometimes strays away from ‘The Frontman’ and rather uses his persona as an entry point for a broader critique of development efforts, campaigning and celebrity engagement that go far beyond the power of an individual or any strategic intentions he may have. That’s perfectly fine, although as I mentioned at the beginning, for those with some interest in the topic it may become a bit redundant.

In the end, this is another great contribution to a series that manages to find the right balance of sometimes polemically engaging with ‘front men’ of development and at the same time holding a mirror in front of us to critically check our own standpoints and comfort zones of how much ‘social change’ we really want and how our discourses have become celebritized, mediatized and professionalized without challenging the foundations of inequality and ‘underdevelopment’.

Browne, Harry: The Frontman: Bono (In the Name of Power).

ISBN 978-1-78168-082-7, 179 pages, GBP 6.99,

Verso Books, London, 2013.

ISBN 978-1-78168-082-7, 179 pages, GBP 6.99,

Verso Books, London, 2013.

Comments

Post a Comment